"In 1965 The Beatles' recordings had been progressing quite nicely thank you, but here was a quantum jump into not merely tomorrow but sometime next week."

That's how Beatles historian Mark Lewisohn sums up the recording of 'Tomorrow Never Knows' in his book The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions. But in truth, you could say the same about much of the album that this song appeared on, Revolver. Its title was apt and the band wasn't messing about — The Beatles really were ushering in a sonic revolution with their 1966 LP.

But what explains this 'quantum jump?' How did The Beatles go from ending their previous album with 'Run for Your Life' — a fairly conventional, country-tinged (not to mention sexist) song that could have appeared anywhere on their previous three albums — to starting work on their new one by recording 'Tomorrow Never Knows,' a psychedelic barnstormer that sounded like nothing that had ever been put on a pop album before?

For me, there are two answers to this question. One lies, as you might expect, with a fundamental change in how The Beatles' wanted to express themselves.

The other is less obvious, and involves the arrival of an unknown 20-year old into the picture.

Let's take a look first at what was going on with the band.

My head is filled with things to say

After releasing Rubber Soul in 1965, The Beatles had embarked on what ended up being their final tour of Britain — but it was a relatively short one, followed by an unusually long period of rest. The band had the first three months of 1966 to themselves — their longest break from recording or touring since 1962.

That's not to say however that all musical activity ceased: in many ways these three months became a research period for The Beatles, especially Harrison and McCartney, who used it to immerse themselves in Indian and classical music respectively.

Lennon, meanwhile, immersed himself in LSD — not just the drug but literature about it too, specifically The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead, by (controversial) Harvard psychologists Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner and Richard Alpert.

This ancient text, designed to be read to the dying to guide them through 'intermediary states between death and rebirth,' was appropriated by Leary and his colleagues to guide LSD users through their acid trips. And their book ended up being a key part of the inspiration for a song, 'Tomorrow Never Knows,' that — as we shall see later — in many ways set the production template for the whole Revolver project.

So by 6 April 1966 — when the first Revolver recording session took place — The Beatles had arrived in a new place. They'd had their first proper rest in years; they had explored new music; and they had tried hallucinogenic drugs. They had the ingredients to hand with which to make a radical record.

And fortunately for the band, EMI Studios had just hired somebody who was perfectly placed to help them with this — a young sound engineer with radical tendencies of his own.

Enter Geoff Emerick

By 1966, The Beatles were the most popular entertainment act the world had ever encountered. So the idea of putting an inexperienced twenty-year old engineer in charge of recording them would in its own right be a fairly revolutionary move. But that's exactly what EMI Studios management decided to do, by promoting Geoff Emerick to be the band's engineer.

Although Emerick had worked with The Beatles before, it was always as an assistant to their previous engineer, Norman Smith. Smith — who had engineered most Beatles recordings up to this point — had been promoted to a producer role, and wasn't too keen on the direction The Beatles were going in anyway, stating that "Rubber Soul wasn't really my bag at all...I decided to get off the Beatles' train."

(Which he duly did, heading off to record Pink Floyd's Piper at the Gates of Dawn.)

Emerick was, by his own admission, terrified by the opportunity and by his relative inexperience, but ultimately said yes to the job offer.

"I remember playing a game in my head, eeny meeny miney mo...The responsibility was enormous but I said yes, thinking that I'd accept the blows as they came."

In fact, it was Emerick's inexperience that was arguably to be his greatest asset during the Revolver sessions. As Abbey Road tape operator Jerry Boys observed, "Geoff walked in green, but because he knew no rules he tried different techniques. And because The Beatles were very creative and very adventurous, they would say yes to everything...[with] another engineer things would have turned out quite differently."

And during the first Revolver recording session, for 'Tomorrow Never Knows,' things were about to get quite different indeed.

But listen to the colour of your dreams

Melodically, it's hard to argue that 'Tomorrow Never Knows' is the strongest track that The Beatles came up with.

But in terms of production, it's one of their most astonishing, and in the context of where pop music was in 1966, entirely shocking. In his wonderful book on the Beatles' recordings, Revolution in the Head, Beatles scholar Ian MacDonald describes it as being to pop "what Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique was to 19th-century orchestral music."

Simply put, there had been nothing like it before in pop. And the same went for the recording techniques involved in its production — there'd been nothing like them before, either.

First off, there was the capturing of that drum sound. Although Beatles drum recordings had gradually been getting more 'focused' — evolving over the years from a cymbal filled cacophony recorded from a distance into a dryer and 'bigger' sound — Ringo had never laid anything down before that sounded so, well, massive.

This was largely down to Geoff Emerick taking a decision to mic his kit extremely closely, stuff blankets inside the bass drum and compress the hell out of the results.

In the context of Abbey Road production techniques, this was an extremely unorthodox way of recording drums — and one that could have technically got Emerick fired, were he not working with the biggest band on the planet (and were they not so impressed with the results).

Then, there were the tape loops. The Beatles all had their own Brenell reel-to-reel tape machines at home and used these to record a variety of sounds — everything from laughter to backwards guitar to clinking wine glasses — which they brought into Abbey Road for use on 'Tomorrow Never Knows.'

Emerick transferred these onto multitrack tape and added them to the song, in his words "[playing] the faders like a modern day synthesiser." These loops all contributed to the creation of an anarchic soundscape that, while perhaps familiar in some ways to listeners of avant-garde music concrete, would have sounded totally alien to 1960s pop fans.

Next, the vocal: for the second half of the song, Lennon wanted to sound like the Dalai Lama and thousands of monks singing from a mountain top. Not having the requisite number of monks to hand, Emerick turned to a rotating Leslie speaker and routed Lennon's vocal through it. Normally used to apply a 'swirling' effect to organ recordings, this was the first time that one had been used on vocals at Abbey Road.

So pleased were the band with this startling, unsettling effect that Emerick noted that "after that, they wanted everything shoved through the Leslie."

'Tomorrow Never Knows' also saw the use of Automatic Double Tracking — ADT — being applied for the first time to Beatles vocals. A tape delay based effect that mimicked the sound of double-tracked vocals, it was invented by Abbey Road boffins to do away with artists having to double track by singing things twice — a laborious process and one that Lennon in particular didn't like. The Beatles were very impressed with this new effect too, and made liberal use of it on the rest of Revolver.

Finally, there was the Indian influence — in the form of a tamboura drone. The inclusion of this was a George Harrison suggestion; Emerick close-mic'd Harrison playing a single note on this instrument, looped it, and added it to the track's increasingly strange audio collage (it ended up as the sound that opens the song).

Although The Beatles had flirted with Indian instruments before — Harrison playing a sitar on 1965's 'Norwegian Wood' — the tamboura sound on 'Tomorrow Never Knows' was far more psychedelic and disorientating than the simple lick deployed on its Rubber Soul cousin.

Ultimately it was fortuitous that 'Tomorrow Never Knows' was the first song recorded for Revolver. Because it was such a strange beast, capturing it required a strange approach — one that forced the band and its production team to explore a range of recording techniques that had never really been used before in pop.

The significance here is that these new recording techniques set the tone for Revolver and they ended up being deployed, in some shape or form, on every one of its songs.

Think of the super close mic-ing applied to the strings on 'Eleanor Rigby,' the tape loops on 'Yellow Submarine,' the backwards guitar on 'I'm Only Sleeping,' the heavily compressed drums on 'She Said She Said'; and ADT sprinkled everywhere — some part of the revolutionary production of 'Tommorow Never Knows' seeped into every corner of the Revolver album.

It's hard to overstate the importance of Emerick's sonic contributions here. The whole sound of Revolver has his fingerprints all over it, and it's why I argue that in many way he was as much of a producer as an engineer to the band.

Lyrics

So production wise, Revolver was revolutionary — but could the same be said of the lyrical content of its songs?

For me, the answer here is yes and no.

In the case of the songs written by Lennon for this album, there is an unambiguous leap away from the boy-meets-girl type of lyrical content that was the hallmark of nearly all of The Beatles' output from 1962 until 1965. His Revolver songs don't really deal with romantic relationships at all.

He gives us no conventional love songs, and with the exception of 'And Your Bird Can Sing,' the lyrics of the songs where Lennon is the primary writer are all, in one or way another, about drugs.

So as far as Lennon's lyrics for this album go, yes, they were pretty revolutionary.

McCartney's Revolver tracks, by contrast, do on the whole stick to the boy-meets-girl formula. We get a splendid romantic ballad, 'Here, There and Everywhere,' along with other songs that deal with love in various ways — 'For No One,' 'Good Day Sunshine' and 'Got to Get You Into My Life.'

(In 1997, McCartney told his biographer, Barry Miles, that 'Got to Get You Into My Life' was technically written as an 'ode to pot' — but even if this is the case, it's more easily interpreted as a straightforward love song, and no doubt would have been understood as such by listeners in 1966.)

The big exception here is of course, 'Eleanor Rigby,' which is not by any means a conventional love song — but does still deal with matters of the heart, specifically loneliness.

The divergence in Lennon and McCartney's approach to song subject matter on Revolver is striking, and for me one of the most interesting aspects of the record. On all the other Beatles albums, the pair are more aligned in terms of their lyrical content — broadly speaking both wrote love songs from 1962 to 1965, and songs involving more abstract topics from 1967 to 1969. But on 1966's Revolver, we find that Paul's still in love and John's definitely doing drugs.

(That probably reflects their key interests at the time: Jane Asher and LSD respectively.)

This combination of love songs and psychedelic tracks actually makes Revolver a very, very odd album: it's hard to think of many other records where one minute the band is singing about running hands through the hair of a loved one ('Here, There and Everywhere') and the next describing an acid trip ('Tommorow Never Knows') or an encounter with an amphetamine-dispensing doctor ('Doctor Robert'). And that's before we get to yellow submarines.

So Revolver ends up being a hugely disruptive, significant record — but without ever really revealing an underlying theme or overarching concept. The only unifying force is its eclecticism.

As for Harrison's songs on Revolver, the first thing worth noting about them is that he managed to get more of them on this Beatles album than he did previous ones. While Lennon and McCartney had hitherto capped his songwriting contributions to one or two tracks per album, they let him have three on Revolver. As with Lennon's contributions, none of these are really love songs, dealing instead with taxation ('Taxman') and LSD ('I Want To Tell You' and 'Love You To').

These are all interesting tracks and the most melodically strong of the three, 'Taxman,' was selected to open the album (preceded by a disorientating count-in that in no way reflects the tempo of the song).

Lyrically speaking, 'Taxman' is arguably one of the most mean-spirited songs in the entire Beatles catalogue (trumped perhaps only by the sexist diatribe mentioned earlier, Lennon's 'Run for Your Life'). Who really wants to hear a millionaire rock star moan that he's paying too much tax?

But 'Taxman' is also a hook-laden song featuring a superb band performance (not to mention a particularly good guitar solo from McCartney). And even if politically objectionable (to this listener at least), the words of the song are nonetheless a lot more interesting — not to mention wittier — than the last lyrics listeners had encountered from Harrison (in 1965's fairly anodyne 'If I Needed Someone').

The art of Revolver

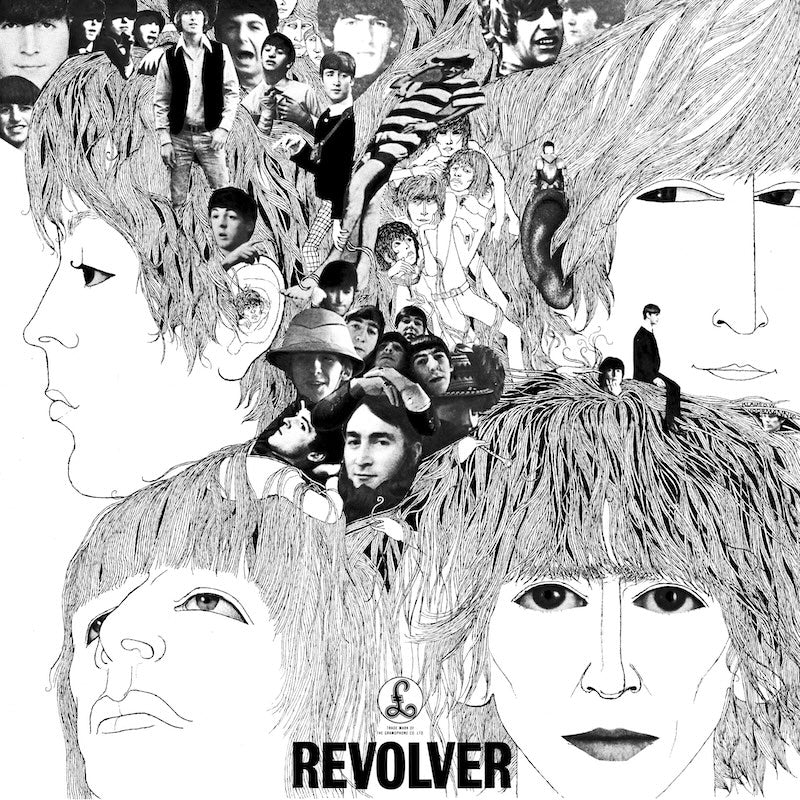

Revolver didn't just represent a sonic break with The Beatles' past — its artwork provided a visual one, too. While all The Beatles' previous album covers had been fairly straightforward photographic affairs, Revolver's was based around psychedelic drawings and collages.

Created by Klaus Voormann, their friend from Hamburg days, for the princely sum of £50, the artwork was also striking for its exclusively black-and-white nature. This was distinctly at odds with the colourful pop art design trends of the time, and helped Revolver stick out from other LPs in record shops.

Interestingly, in much the same way that 'Tomorrow Never Knows' created a production philosophy for the other recordings on Revolver, it may have been informed the development of the album's artwork too. Speaking to The Guardian, Klaus Voormann had this to say about hearing the track for the first time:

"So the band all asked me to come down to Abbey Road Studios. This was when they had recorded about two-thirds of the tracks for that album. When I heard the music, I was just shocked, it was so great. So amazing. But it was frightening because the last song that they played to me was Tomorrow Never Knows.”

Voormann felt that 'Tomorrow Never Knows' was "so far away from the early Beatles stuff that...the normal kind of Beatles fan [wouldn't] want to buy this record" — and designed the cover without the 'normal' kind of Beatles fan in mind.

Voormann's avant-garde design suited the band's sonic move away from their past perfectly; and from Revolver on, the covers of Beatles LPs (with the exception of Let It Be) were to become as much of an artistic statement as the music they contained.

The release and its legacy

Revolver was released on 5 August 1966, to near universal acclaim; critics agreed with its punning title that yes, it really did amount to a revolution. Melody Maker declared it would "change the direction of pop music;" Record Mirror described its songs as "some of the most revolutionary made by a pop group;" Gramaphone described its tracks as "an astonishing collection."

For me though, Revolver's most significant legacy lies in the effect it had on recording techniques. The songs on the album were always likely to be good — we're talking about The Beatles, after all — but, especially where McCartney's were concerned, they weren't all revolutionary.

The revolution was in the production. An entirely new recording language was created on Revolver, for which our friend Geoff Emerick deserves far more credit than he typically gets. A language that shaped not just this album, but how The Beatles (and so many other musicians) recorded afterwards.

In a way, The Kinks' Ray Davies may have underlined this point — and inadvertently given Geoff Emerick that production credit — when he gave the world his take on 'Tomorrow Never Knows':

"Listen to all those crazy sounds! It'll be popular in discotheques. I can imagine they had George Martin tied to a totem pole when they did this."

Listen to all those crazy sounds indeed.

Related articles:

Why Did The Beatles Break Up?

The Making of David Bowie's Hunky Dory

About the author

Chris Singleton is the songwriter in Five Grand Stereo and a regular contributor to this blog. When not writing music — or about it — he edits a popular blog about ecommerce and web design, Style Factory.