1971: the year that changed everything

On June 8, 1971, David Bowie went into Trident Studios in London’s Soho and began recording Hunky Dory. Some two months later, that magnificent album was in the can, but Bowie’s thoughts had already turned to marshalling his troops once more and getting to work on its follow-up, which ended up with the title The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars. There is even evidence he was feeling so energised by the happy experience of recording Hunky Dory that he felt a double album might be on the cards.

Let’s skip forward to August 1972. David Bowie (a.k.a. Ziggy Stardust) has finally become what for so many years he dreamed of becoming: a bona fide rock god. He gives an interviewer the following account of what it was that made last year the breakthrough one that would transmogrify him from an all-but-forgotten one-hit wonder (the Ivor Novello-winning ‘Space Oddity’, 1969) into the brightest new star in the rock firmament:

"I went to the States for three months to promote The Man Who Sold the World and when I returned I had a whole new perception on songwriting. My songs began changing immediately. Secondly, by the time I came back I had a new record label, RCA, and also a new band. America was an incredible adrenaline trip. I got very sharp and very quick. Somehow or other I became very prolific. I wanted to write things that were more immediate."

There is only one problem with the compelling story Bowie tells here of how the stars aligned perfectly for him: it’s not really true. 1971 — the year in which he reinvented himself and recorded two knockout albums — was a good deal messier than that.

For one thing, the promotional tour of the States had lasted not three months but just one: Bowie flew into Washington D.C. on January 23 and was back in Blighty just twenty-seven days later. When he arrived in the States, he was pretty much unknown in America; by the time he got back home, he was pretty much unknown in America.

For another thing, the record deal with RCA did not come together until months after his return from that trip.

And no, he didn’t have his new band in place by the time he came back. On the contrary, his crack soldiers Mick Ronson and Woody Woodmansey had given evidence of pronounced commitment issues at best, a dispiritingly post-Bowie outlook on things at worst. The musical team behind Hunky Dory did not come together until June.

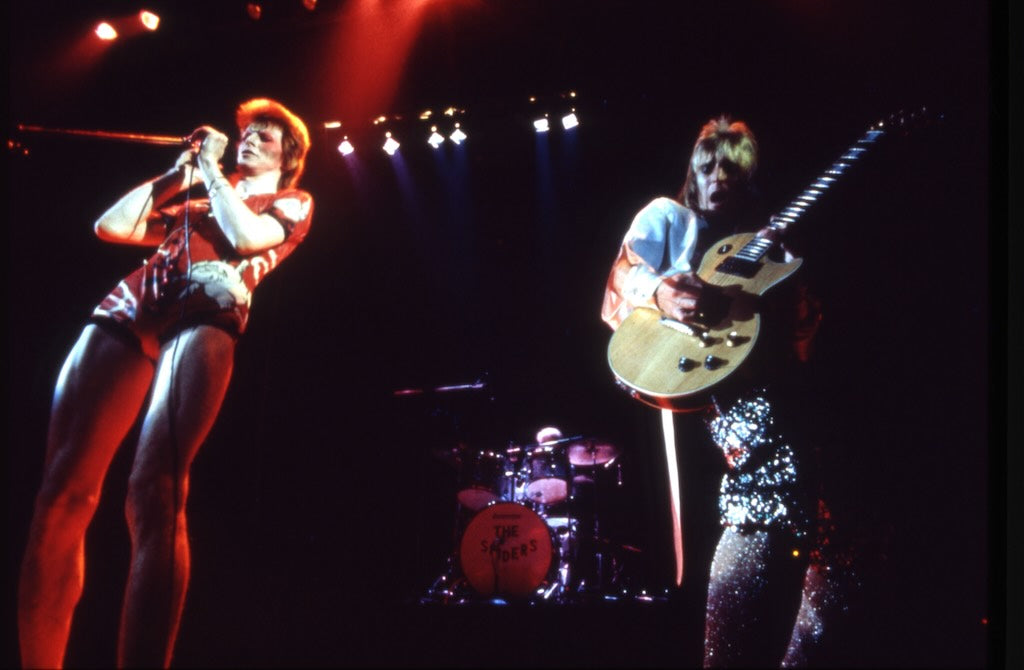

David Bowie and Mick Ronson performing in 1972. Photo: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy

These are not minor details. If you had come across this struggling befrocked artist in the weeks following his return from the States and asked him about his future in the music business, chances are he would have talked down his prospects of making it as a star and talked up his plans for becoming a top-tier songwriter for hire.

There is however an important nugget of truth in what the brazenly self-mythologising Bowie told that journalist in August 1972: the Stateside promotional tour really did blow his mind. The David Bowie who came home may have been a man still mortifyingly Not Nearly Famous Enough, but he was a man on fire with new and intoxicating insights into the weird grammar of songwriting, stardom and cultural impact.

Once home, however, it took quite a while longer than Bowie would see fit to let on in August 1972 for objective conditions to catch up with subjective excitement.

Divine symmetry: the road to Hunky Dory

Looking back at the astonishing trajectory Bowie took between touching down in England on February 18 and kicking off the Hunky Dory recording sessions on June 8, a number of things jump out.

First off, there’s the Stevie Wonder non-event. It is arguably the single most important factor in the whole story of Bowie’s ’71 comeback.

Let’s back up a moment. Bowie had parted ways with his manager Kenneth Pitt in 1970 and was now being looked after by Gem Music Group. Except…he wasn’t being looked after in anything like the fashion he needed. The evidence suggests that he was, in early 1971, far from a priority for his manager Tony Defries. What was getting Defries’ pulses racing in this period was the possibility of adding Stevie Wonder to his roster. Little Stevie would be turning twenty-one in May, which would mean the lapse of his contract with Berry Gordy’s Motown, a home he was telling people he wanted to leave.

In the end, Stevie broke Defries’ heart by opting to stick with Motown. This decision on the far side of the Atlantic would prove game-changing — for David Bowie. It made the disappointed Defries sit up and pay attention in a new way to his young charge much closer to home. For Defries wanted one thing above all else: to nurture to the toppermost of the rockermost the Next Big Thing, whoever that might turn out to be.

It helped that Bob Grace, Bowie’s publishing guy at Chrysalis Music, had (along with radio plugger extraordinaire Anya Wilson) been gamely trying to keep the Bowie torch lit all the while. Grace’s most crucial intervention had come on January 20, when he had played an acetate of Bowie’s demo of ‘Oh! You Pretty Things’ to top independent producer Mickie Most at the MIDEM festival in Cannes. Most declared the song “A smash!” on the spot, and before too long Peter Noone (ex-frontman of Herman’s Hermits) was on Top of the Pops gifting posterity with one of its all-time funniest archival moments: a cute-faced pop boy-next-door singing glam-Nietzsche lyrics about making way for the Homo Superior, and with such endearing innocence you would think the H-word only had one possible meaning.

In any case, Mickie Most’s snap judgment on ‘Oh! You Pretty Things’ stood vindicated: the song did good business. Bowie found himself the writer of a UK chart hit, the first to bear his imprint since the long-distant tale of Major Tom losing contact with Ground Control.

This wasn’t his only foray into the Cyrano de Bergerac strategy of enlisting a dreamboat to front for his creative output. Around the same time, he was perpetrating a benign hoax on the record-buying public by manufacturing a band called Arnold Corns. The supposed frontman was someone who couldn’t, as it were, sing: 19-year-old Freddi Burretti (a.k.a. Rudi Valentino), Bowie’s unfeasibly fabulous tailor pal from the Sombrero gay club. Bowie had Burretti take the credit for Bowie’s own vocals on a single release of Bowie’s own compositions ‘Moonage Daydream’ and ‘Hang on to Yourself.’

Bowie went so far as to tell one interviewer: “I believe that the Rolling Stones are finished and that Arnold Corns will be the next Stones.” The single tanked. He also got Mickey (‘Sparky’) King to record his car-themed novelty song ‘Rupert the Riley’. The track wasn’t even released.

The very fact that Bowie was going for this kind of ploy suggests that a Plan B for his own musical career, one that involved his taking on a more behind-the-camera role, was very much in formation. It cannot be forgotten that his wife Angie was heavily pregnant by this point (their son Duncan Zowie would be born on May 30), and Bowie had to face the inglorious need to secure their financial future.

By the time Noone’s ‘Oh! You Pretty Things’ reached #12 in the U.K., the Hunky Dory sessions were already under way. Had this success come even a month or two earlier, it might well have represented a real danger for that song’s writer. Bowie had been in the business some eight years by this point, both fronting a succession of bands and trying to get arrested as a solo artist. He had made no fewer than three albums, and seemed as far away as ever from the kind of enduring stardom he had always felt was his due. ‘Space Oddity’ had heralded not the painfully late beginning of a supernova ascent but an aftermath period marked by the anguish of anti-climax and waning interest.

Now finding himself uncomfortably far on the wrong side of eighteen or even twenty-one (he had reached the ripe old geriatric age of twenty-four), and having just watched his friend/rival Marc Bolan go all the way with T. Rex, he honestly wondered if it would ever really happen for him. Unbelievable as it may seem to us at this historical remove, with all we know of his once-in-a-generation voice and his iconic presence, he seems to have wondered if the wiser course might not be to relinquish his dream of primary stardom in favour of the quieter role of backroom musical genius to the stars.

At least he’d be making a decent living.

Thankfully, Bowie’s self-belief as singer and performer proved robust enough to trump the temptation to lose himself in any such proxy game of basking in the reflected glory of others. He was not Lionel Bart, nor was meant to be. It seems that, in the perilous no-man’s-land interim between returning from the States and entering Trident to record Hunky Dory, something went click in Bowie’s head. He came to the realisation that there might after all be enough movement on his own shoulder for him to lay claim to the post-Beatles crown. If he got this right, Marc Bolan would look in retrospect like a mere dress rehearsal for The Bowie Show.

Here, one feels, is where the American trip earlier in the year came into its own. Bowie experienced New York, L.A. and points in between as a zone of openness, a place where anything could happen — or rather, anyone could happen. He met characters such as one might encounter in a movie. He saw the primitive power of being different. The songwriter in him registered anew the power of noticing and celebrating the outrageously different.

Americans, in short, seemed less afraid to go for it. ‘Pick your character,’ the lesson seemed to be, ‘pick your cabinet of talents, and — above all — lose every last vestige of your very British self-consciousness. It’s a malleable world out there, kiddo, so lighten up.’

Bowie left the country with a redoubled sense of the possibilities of an unapologetically calculating fame-making strategy, but one grounded in exceptional and exceptionally idiosyncratic songwriting craft.

Perhaps this is at least part of what is going on with the Freddi Burretti, Mickey King and Peter Noone experiments. Bowie is feeling his way towards the new and more grandiose conception of his public self and of his musical talents that will culminate in Ziggy. It’s just taking a minute for the impact on him of America to be absorbed in full. In March he even wonders aloud in an interview with Disc and Music Echo whether a move to America might not be the only way for him to salvage his recording career.

By the time he gets to work on Hunky Dory, however, he has not just written the screenplay for the movie he wants to see, he has also decided to star in it himself, with shooting to go ahead on native soil. Crucially, though, his rising sense of his own viability as a commercial songwriter means that he has an insurance plan to fall back on if need be: he knows that he can, if it comes to it, do well writing songs for others.

The David Bowie who enters Trident is thus a man who has at once raised the stakes and taken some of the pressure off himself by spreading his bets. He still dearly wants to be a star, but the alternative is a worst case scenario that would at least allow him to achieve some species of musical renown.

Which is where the timing of Tony Defries’ Stevie Wonder disappointment seems so providential. Bowie cannot auto-suggest himself into stardom in a vacuum. Not even the indefatigable moral support of the fearlessly bohemian Angie can bestow upon him the gift of rain-making. He needs a visionary manager who truly sees his client’s star potential.

Once Defries comes on board for real, the elements for epic levels of success are in place. The David Bowie that has been taking shape — ex-mod ex-hippy androgynous bisexual bichromatically-eyed jagged-toothed love child of Oscar Wilde and Greta Garbo; artistic provocateur of the very first water; songwriter with a proven track record of hit-making capability; Anthony Newley-influenced singer of no mean range, control and expressive power; ravenous culture vulture whose Cosmic Curiosity Shop brain yields lateral lyrical brilliance with seeming ease; charismatic magnet for beautiful outsiders, freaks and outlier sensibilities...is ready once more to give Plan A his best shot.

And so it is that a galvanised Defries hatches a scheme. It is bold and it is brilliant. Bowie’s contract with the underdelivering Mercury/Philips record label is coming up for renewal. This is Bowie’s chance to break free and start over with a new and vastly more promising record deal. But for that to happen on the terms Defries believes necessary, Bowie must first record an unanswerably strong album. Gem Music will finance the sessions, and then Defries will use the album as leverage in his negotiations with labels.

As Bowie enters Trident Studios on June 8, it’s all to play for.

Put you all inside my show: recording Hunky Dory

If we lay aside all non-musical factors informing the Hunky Dory sessions, three things that testify in a special way to Bowie’s genius come into focus.

One: the team he assembled.

Mick Ronson back on guitar (“my Jeff Beck,” as Bowie liked to say) and now trying his hand at string arrangement too. Woody Woodmansey back on drums. Trevor Bolder on bass. Rick Wakeman on piano (and not just any piano: the 1898 Bechstein Paul McCartney had played on 'Hey Jude'). Ken Scott on co-production.

Bowie trusted them. He gave them their head in the studio. He knew better than to micromanage them. As he would admit a couple of years later, “I’m not a musician. I play composer’s guitar, composer’s piano, and a little bit of sax."

The album credits for Hunky Dory

This humility on the chops front allowed him to cherish the superior musicians in studio with him. He knew they could take his songs to the place they needed to go. As for Scott, Bowie had worked with the Beatles veteran before, and greatly respected his technical know-how and shrewd ear. Scott had recently worked as engineer on George Harrison’s acoustic-guitar-rich All Things Must Pass, a circumstance that no doubt helped steer Bowie’s new album clear of the forced muscularity that had at times marred The Man Who Sold The World.

By (nearly) all accounts, the sessions were convivial and good-humoured. But Bowie set the bar very high when it came to takes. He wanted not studied perfection but dynamic vitality. The band were very quickly given to understand that an unofficial three-takes-max policy was in force. Let’s hope we get it on this first take, boys, but it may go to a second — and, at a pinch, a third. This was pressure of the very best sort, and the boys met the moment. They committed. They had no choice. To say that the album owes much to the resulting freshness and back-to-the-wall resourcefulness of the band’s ensemble playing would be putting things at their very mildest.

Just as Bowie kept his musician-ego in check and let the guys place their individual and collective stamp on his songs, so too did they bring talent rather than ego to bear upon the songs. They served the songs with great intuition and discrimination, knowing just when to hang back, when to up the ante. And few would dispute that Ronson, beyond his own sterling guitar parts and string arrangements, played a key unofficial co-co-producer role in helping Bowie and Scott get just the right amount and flavour of juice from each song.

Two: Bowie’s own performance as vocalist.

When the band first became aware of his three-takes-max rule for them, the suspicion was that he wanted to hog as much time as possible for his own vocal takes. Not a bit of it. According to Ken Scott, Bowie showed an almost uncanny discipline and focus once the red light went on. He established a remarkable norm for himself: one take will probably be enough, maybe two.

On several occasions, as Scott recalls, the team up in the control room would listen to him do a take and wince as they heard mistakes. Bowie would come upstairs to them afterwards and, hearing talk of wrong notes and the like, ask for the tape to be played back. Only then would they realise that those wrong moments were not just deliberate — they were righter than right.

To me, this detail — more than any other — speaks to Bowie’s courage and poise in the Hunky Dory sessions. As any vocalist knows, the studio can be an intimidating place. Time, after all, is money. The red light goes on, and you start fretting over the when and how of breathing, the regulation of saliva, the goblins of pitchiness. And yet here we have David Bowie, a not terribly successful recording artist whose very career prospects hang on the outcome of these sessions, taking to the mic with all the cabaret abandon of John and Paul in the Get Back sessions. Unlike them, he does not have the luxury of endless takes. Nor, like singers these days, is he residing in the Land of Digital Comp: he actually has to sing the whole song through as though he’s up on stage, right smack in the middle of the Now or Never Zone.

(Contrast this with a fact recalled by Peter Noone: back in late March, Bowie needed to record his piano part for the Noone/Most version of ‘Oh! You Pretty Things’ in three separate sections.)

All of which is a long way of saying that Bowie is singing as if he has already made it as a star, and is more than happy to share some of the fruits of his prodigal genius with a grateful world. In his head, he has done the one thing most needful, which is flip the paradigm from “I need you to like me” to “You need me to do this.” This is a young man with an attitude solution.

We get a nice glimpse of Bowie’s sovereignly relaxed attitude at the mic at the start of ‘Andy Warhol’. Scott names the take, and Bowie corrects his pronunciation of the surname. He’s not being nervously irritable; he’s not being precious; he’s just engaged and in good humour. And, across song after song, we marvel at the go-for-broke brio of his vocal renditions: this is the sound not of a singer anxious to get a good take but of an artist in love with the song.

Three: it’s the songs, stupid.

All the songs bar one (Biff Rose’s ‘Fill Your Heart’) were written by Bowie, whose songwriting for this album was substantially piano-based. He had got his hands on a second-hand grand from a neighbour (arguably the best use of £50 in popular music history), and had in recent months been on a songwriting spree in ‘Beckenham Palace’— his nickname for Haddon Hall, the grand old Victorian house in Beckenham where he and Angie rented a flat and held court.

The move into self-taught piano songwriting made a telling difference. Never exactly a slouch in the chord progression department, Bowie now went up another gear or two in harmonic sophistication and surprise. Being unversed in the intricacies of bass and treble clef, he let his fingers wander to hitherto unthought of places — and he let his theory-innocent ears decide which of those places were good, which rubbish. He took childlike delight in throwing dissident notes on top of the usual triads, lending many a chord a delectably strange new colouring beyond what even he might have ventured on guitar.

(Fun fact: the writing of ‘Oh! You Pretty Things’ was complicated, and enhanced, by the the piano’s having a stuck note — Bowie had to contrive on-the-spot workarounds.)

Listen for example to his homemade demo version of Changes, the song that would open Hunky Dory. One is struck by just how finished the composition already is. True, he’s largely block-playing the chords, which still await the magic Wakeman touch. But what chords they are! The intro alone is just plain illegal: Cmaj7 to D♭6 to Dm7 to E♭7.

The partial switch from battered old 12-string-guitar to piano allows Bowie to cultivate a musical ambition and audacity commensurate with the ambition and audacity of his (extensively) post-America lyrics, which might otherwise have risked coming across as forced and pretentious. He earns the right in a new way to go magnificently rogue with his words.

As such, he is carving out an aesthetic space for himself rather different from that carved out by a rock titan he namechecks on the album: Bob Dylan. Where Dylan will tend to cleave to a three-chords-and-the-truth ethos in service to his lyrical shenanigans, Bowie is attempting what perhaps only Lennon and McCartney have pulled off before — thirteen chords and the modernist poem.

But even here he shows great artistic tact. He knows when to turn and face the chordally strange, but also when to go easy on the changes. Songs like ‘Changes’ and ‘Life on Mars?’ astonish the ear with their twists and turns; part of what makes songs like ‘Eight Line Poem’, ‘Kooks’, ‘Queen Bitch’ and ‘The Bewlay Brothers’ work is the fact that their creator is letting them breathe on the chord front. It would be hard to imagine, say, ‘Queen Bitch’ coming off with a more jazzy chord progression: quite apart from the Velvet Underground vibe that would be lost, the savage vocal part (an inspiration, surely, for The Killers’ ‘Mr. Brightside’) would lose its bite.

Further proof of Bowie’s sound judgement as Hunky Dory’s songwriter may be found in the fact that, in the run-up to the recording of the album, he liked to sit people down and play them the new songs on guitar. For all that he was enamoured with the new ebony-and-ivory weapon in his compositional arsenal, he saw that each song still had to pass the busking test: could it hold its own when sung and strummed without embellishment?

Canvassing the various recollections given over the years by those who took part in the Hunky Dory sessions, it is hard not to feel that everyone — starting with Bowie himself — believed in these songs a lot more than had been the case with The Man Who Sold The World. There is an abyss of difference between turning a song idea into something good in the studio and doing full justice to an already great song in the studio. The intrinsic quality of the ready-baked Hunky Dory songs gave Bowie the confidence to go into Trident that summer with a level of Zen serenity that was not yet supported by his objective status out in the music-biz world. And the challenge that confronted Ken Scott and the musicians was not that of making a strong album out of serviceable materials brought to the table, but that of not letting these extraordinary songs down.

Bowie's on sale again: the end of the new beginning

In September 1971, Bowie flew back to the States to sign with RCA Victor. In the space of less than a year he had gone from increasingly isolated has-been-wannabe to rock’s hottest ticket.

The seed for Defries’ coup in securing a deal with RCA had actually been sown by Bowie himself in L.A. back in mid-February, when he had told RCA man Tony Ayres of his frustration with his current record label. Ayres spoke encouraging words about RCA’s need to find a superstar successor to Elvis Presley, who (in Ayres’ words) “can’t last forever.” He can hardly have realised in the moment just how prescient his words were, and not just on the score of the ageing Presley’s commercial and actuarial prospects: the well-spoken, personable and strangely-dressed English underdog he was speaking to would soon turn out to be none other than the Seventies’ own generation-liberating answer to The King.

Hunky Dory, the rejuvenated Bowie’s calling-card album, was released in December of that year. While well received critically, it would take some time for the record-buying public to give it the attention it so richly deserved. (‘Changes’ was released as a single on January 7, 1972, and flopped; the equally but differently superb ‘Life on Mars?’ didn’t become a single until 1973.) Bowie’s Ziggy character first needed to launch him into the stratosphere. What we are hearing on Hunky Dory is the sound of countdown being commenced, and engines very much on. Ask any hardcore Bowie fan these days to name their top three Bowie albums and chances are Hunky Dory will make the list. It is widely regarded as a superior work to Ziggy.

The reviewer of Hunky Dory for the New Yorker hailed Bowie as “the most intelligent person to have chosen rock music as his medium.” He was hardly being hyperbolic. The album’s sheer brilliance, at every level, showed anyone who was paying attention at the time that this artist was that rarest of rare exotic birds: a self-proclaimed “faker” of formidable substance.

Like Wilde a century before, Bowie could play so well with surfaces precisely because he had so much depth. No less importantly, the David Bowie who entered Trident on June 8 was a man who understood very finely the respective claims of ego and humility. By all means turn and face the strange, but if you want to get anywhere you’re going to need damn good songs, damn good musicians, a damn good co-producer, and a damn good manager with a damn good plan. Don’t fake it till you can make it.

You might also enjoy:

- David Bowie Movies — A Guide to All His Cinema Roles

- The Making of The Beatles' Revolver

- The Making of Pink Floyd's The Dark Side of The Moon

About the author

Daragh Downes is a writer, critic and musician. He has written music features and reviews for The Irish Times and has discussed musical, literary and cultural matters on Irish national radio. For many years he lectured on literature, aesthetic theory and cultural history at Trinity College, Dublin.

2 comments

Hunky Dory was an album I found after Ziggy Stardust, but very quickly became my favourite. For years I was handing out mix tapes with Hunky Dory on the A side, with the B side playing… Transformer by Lou Reed. I never once had a negative response to this pairing. Often I would hear from friends it was played so often in their cars it would eventually snarl up and did I have a replacement?

I suggested they buy both albums to get the best sound clarity (remember tape hiss!) as there was much more detail to be heard.

I’m now in my 60’s and it’s so good to hear serious musicians point to these albums as must have’s in any album collection.

Amazing to think this was the early 70’s.

Interesting that you end by saying “Don’t fake it till you can make it.” because, from what Woody Woodmansey says, that is precisely what he did with the first US RCA tour. Bowie was still relatively unknown in the USA but Defries talked RCA into funding a tour that gave the impression that Bowie was a huge star gracing the USA with his presence. They stayed in expensive hotels and acted like superstars in public. By all accounts RCA were very nervous but Defries kept them happy just long enough for it to pay off :-)