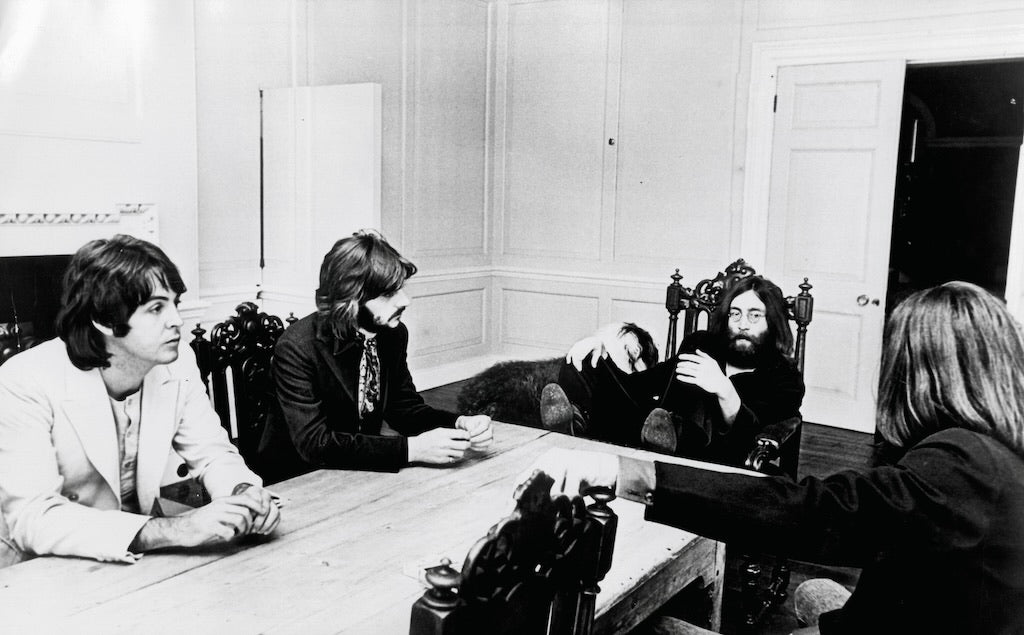

At the end of the Sixties, the biggest band in the world fell apart. Who — or what — was to blame for this?

Let’s start by looking at two of the usual suspects, exploring the merits and demerits of the case against each. Then we will explore a less frequently considered alternative solution to this whodunit.

Yoko Ono?

Yoko Ono. Photo: Gijsbert Hanekroot / Alamy

The ‘Yoko Did It’ story is easily narrated: she comes along and turns Beatle John into a weird new creature called Lennono.

Under her nefarious sway, John goes from an enthusiastic and fantastically creative member of the Fab Four to a man who sees his salvation as lying elsewhere altogether — in an intensely close personal relationship with this avant-garde artist. The more real this love feels, the more unreal the whole Beatles world comes to feel. The more Yoko is attacked, the more loyally John sticks to her.

She has even taken to sitting in on Beatles recording sessions, her inhibiting presence and entitled behaviour a source of intense annoyance to Paul, George and Ringo. They are no longer touring, so the studio now represents pretty much the totality of their shared world. The camaraderie between the four ‘boys’ is thus fatally weakened by Yoko’s presence, with the result that they find it increasingly difficult to hold things together. It’s no longer John, Paul, George and Ringo but Lennono, Paul, George and Ringo. This is not a functional unit. Any Beatle not madly in love with Yoko finds himself trapped in an intolerable situation. Each will act out his angst over her intrusion into the group’s life in different ways.

At the heart of this ‘Yoko Did It’ story is of course her effect on the relationship between John and Paul: she supplants Paul as John’s co-partner. The Paul we see in Peter Jackson’s Get Back documentary is that most bewildered and wounded of creatures, a jilted man. He still wants John, but it is becoming painfully clear that John has chosen Yoko. Worse still, she is proving to be more than just another of John’s passing phases. This lady is here to stay.

There are, it is true, still flashes of the old John-and-Paul magic, but if anything they only point up the sadness of the situation. A love that should have lasted years, but John has convinced himself that he no longer needs Paul. We watch a crazy jam between John on guitar, Yoko on screech, and Paul on drums, and wince: “Look, John,” Paul seems to be saying in desperation, “you don’t have to choose between her and me — you can have us both!” But the sound they’re making tells him this is one throuple that has no future.

“Damn,” runs the perennial BeatleFan thought, “if only she hadn’t come along, they could have kept going.”

But just how valid is this accusation against Yoko?

Well, let us at least give an airing to a counter-factual thought: had Yoko not come into John’s life when she did, there is every chance he would not have even made it to January 1969.1968 could so easily have seen him secure his place in music history as the most famous member of the 27 Club. He could have gone the way of poor Brian Epstein and succumbed to overdose (accidental or otherwise).

Emotionally and psychologically, John was in the deepest of deep trouble in the period following the band’s decision to stop touring. ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ is the sound of a damaged genius overwhelmed by his own sole self. The demons raised in ‘Help’ have not just not gone away, they are more giddy than ever. And just listen to the lyric of ‘Yer Blues’:

Well I’m lonely,

Wanna die,

Yes I’m lonely,

Wanna die,

If I ain’t dead already

Girl you know the reason why.

We know full well who ‘Girl’ is here, and have little warrant for thinking that John is merely throwing self-pitying blues clichés at his blues-rock workout. No — this is John in naked self-confessional mode. And it would be foolish to assume that he is overstating just how close to the edge he has come of late. A few years later he will sing to her:

Anyway I survived

Long enough to make you my wife.

He really believes this, and who are we to tell him he doesn’t know what he’s talking about?

All of which invites us to look rather differently at the fact of Yoko’s ever-presence with John in Get Back. For one thing, she is not there uninvited: John has been insisting for some time now that she accompany him everywhere he goes. He is clinging on to her for dear life. The little child inside this man is terrified of being abandoned all over again. With her, he may be a much more unreliable and mercurial Beatle (and one hooked on heroin), but at least he’s somewhat functional. Without her, he’d be a total basket case — or not even around anymore. The White Album, or even Pepper, could quite easily have turned out to be the last full Beatles studio album. Everything since, on this view, has been a merciful bonus. Because — he survived.

Thus, perhaps, the real human pathos of what we’re seeing in the Get Back documentary. John is in company with the two people who have saved his life. Paul came along in 1957 and gave him a viable way of keeping his personal despair at bay. A decade later, with diminishing psychological returns having already set in on the Paul ’n’ Me partnership, Yoko comes along and offers John a new identity into which to sink his ego. It will arguably be the thing that — with one sustained period of separation — keeps him alive until 8 December, 1980.

(But even there we have troubling evidence that, during the latter Dakota years, things will be dangerously touch and go with John on the existential despair front. Just read The Last Days of John Lennon, the revelatory memoir by John’s personal assistant Fred Seaman. Or take a listen to John’s demo of the chilling ‘Help Me To Help Myself.’ Has the law of diminishing returns kicked in once more? Might John be feeling his way to a new — or even old — escape route out of his pain in the Eighties? Thanks to the “jerk of all jerks,” who shall remain nameless, we will never know. What we do know is that, towards the end of John’s life, Yoko is actively blocking Paul’s calls to John. What exactly can she be afraid of?)

Allen Klein?

Allen Klein (left), with John Lennon and Yoko Ono. Photo: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy

In January 1969, just at the time The Beatles are encamped in Apple Studio at 3, Savile Row continuing work on their Get Back songs, New York businessman Allen Klein meets John and Yoko at the Dorchester Hotel. He charms the socks off them both and soon John, George and Ringo — but significantly, not Paul — are all in favour of appointing him Beatles manager. As Ringo puts it, he will be “a conman who will be on our side for once.” He promises to do for them what he has already done for The Rolling Stones: forensically go through the accounts and identify deliciously large sums of untapped money for his clients.

The ‘Klein Broke Up The Beatles’ charge can be summed up thusly: he was a talented shark who took advantage of The Beatles’ financial woes to insert himself into their affairs, in the process driving a fatal wedge between Paul and the other three Beatles. By the time John, George and Ringo had realised their mistake, several years later, it was way too late.

This summary, it seems to me, is at once fair and insufficient.

Fair, because Paul would be largely vindicated by ensuing events, with John, George and Ringo eventually turning on Klein too. Furthermore, Paul’s own management team of choice (Lee and John Eastman, his father-in-law and brother-in-law respectively) would go on to prove their worth by serving his financial interests to supreme effect through the creation of MPL.

Insufficient, however, because of the great given that made Klein seem such a beguiling prospect to John, George and Ringo in the first place: the utter disarray in The Beatles’ financial affairs as of January 1969.

Long before Klein entered the picture as the band’s wannabe-manager, they were prey to financial sharks. Brian Epstein’s tragic death on 27th August 1967 deprived them of a visionary and dedicated talent manager, but the void left by his death revealed to them more and more just how poorly he had protected their financial interests.

Under his guidance, for instance, they signed a lousy publishing deal with Dick James, and a truly catastrophic Seltaeb merchandising deal with Nicky Byrne. This latter fiasco would be glossed with depressing accuracy by Paul in a 1981 conversation with journalist Hunter Davies: “We got screwed for millions…It was all Brian’s fault. He was green”. (The total sum of money lost by The Beatles as a result of Epstein's ineptitude in the Seltaeb negotiations has been estimated at some $100 million.)

The Beatles’ own disastrous Apple foray in 1968 only exacerbated the already parlous financial position in which Epstein had left them.

And yet, and yet…here too a counter-factual thought experiment can yield unexpected insight. Just suppose Epstein had played hardball in every aspect of The Beatles’ financial affairs. Wouldn’t that have given them a much bigger piece of the pie? Not necessarily. It might well have made the pie itself much, much smaller. For the rise of The Beatles may have happened — in part — because he was such a pushover on the financial front. His naivety and weakness at securing optimal financial deals may have proved his strength at getting them a foot on each new rung of the ladder. Exposure and financial optimisation: was there not an element of trade-off between the two? Would they have secured all those live bookings if Brian had driven harder bargains? Would they have bagged that epoch-making first Ed Sullivan Show appearance? Would they have even been signed to Parlophone and Capitol? There is at least room for reasonable doubt here.

The point being that Brian Epstein — the genius impresario who steered The Beatles to undreamt-of levels of fame and success — may in fact have been more instrumental in their eventual break-up than Allen Klein. He made them and he sowed some of the seeds of their unmaking.

Critically, the more the post-Brian Beatles are finding out about his deficiencies as a business manager, the more their own belief in the providential Beatles myth is undermined. The death of ‘Mr. Epstein’ has led to the replacement of innocence with experience. To make a bad situation truly dire, the fraying personal relations within the band at this time mean that they no longer have the old bulwark of group cohesion. This drastically weakens their ability to respond to their financial challenges in a unified and all-for-one-one-for-all fashion.

The Beatles are still superlatively good at one thing: making music. At everything else, they show themselves to be anything from unassured to downright cack-handed.

Magical Mystery Tour is their attempt at self-directing a film, and it is — at least in terms of contemporary public and critical reaction — a disaster.

Apple, their grandiose experiment in ‘Western Communism’, quickly runs aground on its own conceptual incoherence and logistical chaos.

As for their ability to get on top of their finances, watching them go about it is like watching an Olympic ice-skater try their hand at grandmaster chess. Brian Epstein’s shielding of them from the intricacies of his financial deals on their behalf only infantilised them when it came to money matters.

By 1969, they have all come to recognise the urgent need to enlist the ruthless talents of a tough financial cookie. Sadly, they just can’t agree on which cookie to go with. The rest is misery — only part of which can fairly be laid at Allen Klein’s door.

The real culprit?

On the analysis so far, Yoko didn’t break up The Beatles, though she was at the heart of the band’s all too messy demise. Nor did Allen Klein, though his arrival probably accelerated that demise — and certainly added to the terminal acrimony.

If one were forced to identify one factor of which it might reasonably be said, “Without this X having come into play, things could have gone very differently”, one might choose not a person but a synthetic chemical: lysergic acid diethylamide.

It sounds so counter-intuitive. Didn’t LSD open up The Beatles’ collective and individual sensibility? Didn’t it make them even more creative as 1965 turned into 1966 into 1967? Wasn’t its effect especially transformational on John’s artistry, inspiring him to musical and lyrical moves of astonishing laterality? Don’t we have LSD to thank, at least indirectly and in part, for such glories of the creation as ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’, ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’, ‘A Day in the Life’ and ‘I am the Walrus’?

Yes to all of the above. But the toll taken on John’s psyche may have been too heavy to allow the band to hold together in the longer term.

And it wasn’t just John’s altered mind that was in play here. Consider one fact: the two Beatles who became most reluctant to continue being Beatles — John and George — were the two Beatles who had taken most acid. The two Beatles whose hearts were broken by the band’s breakup — Paul and Ringo — had been much lighter partakers.

This may well be no coincidence. The impact of acid on John and George was dramatic: it weakened their respective Beatle Egos. It de-prioritised Beatlehood.

There would be no coming back from this.

LSD opened George up (as he saw it) to spiritual possibilities that made the Beatle existence seem irredeemably worldly, something that only enmeshed him further in the gross relativities of the material world. (That he deeply believed in the truths of Eastern mysticism can hardly be doubted; that he saw no contradiction between this and his own constant whingeing about money can hardly be pondered without a scratch of the head.)

LSD also lent Harrison's lyric-writing a newly philosophical, not to say proselytising, dimension. He more and more came to see his continued membership of The Beatles as justifying itself only if he could use it as a vehicle for raising world consciousness— a mission creep that would unsettle the band’s delicate ecosystem more and more.

As for John, LSD opened him up only to leave him more emotionally and psychologically destabilised than at perhaps any time since his teenage years. As argued above, Paul McCartney’s arrival on the scene all those years ago had rescued him. And now it was Yoko’s turn. But Paul, protective of his amazing friend and his amazing band alike, had other ideas: he was desperately trying to keep John from going under by keeping him focused on being a Beatle. And so he slipped into leader mode, chivvying John and the others into sustaining the work ethic that had taken them to the toppermost of the poppermost and kept them there. John saw this and became increasingly resentful of Paul’s paternalistic attitude. He also interpreted it as an insult to Yoko — and to him for falling in love with her.

Trust, in short, had broken down between John and Paul. To compound the nightmare, their psychodrama only emboldened George to challenge their near-monopoly on songwriting and singing duties. And so Paul became the chief target of his resentment too. As early as the Pepper sessions, George was giving off contradictory vibes: I don’t really care about The Beatles anymore; I really care about being an equal-status songwriter and lead-vocalist in The Beatles.

[Trigger warning: pro-Paul content ahead.]

What was Paul to do here? His honest aesthetic judgement (shared, if truth be told, by John) remained that George could not consistently write and sing songs to the same maestro level as Lennon-McCartney. Was this an unfair judgement? Or was it robust quality control, of the sort that he and John (and George Martin) had always imposed? Paul had an ego, of course. But, unlike John and George, he still saw the incredible power unleashed when one allowed one’s ego be placed in the service of this uniquely magical four-headed creature. He was a perfectionist who celebrated genuine Beatle brilliance, whatever the source. Just listen to his bass playing on ‘Come Together’ and ‘Something’.

Sadly, John and George had increasingly come to resent his brilliance, just as he found himself taking on the grim role of director of proceedings. He felt at times that he was the only person in the room who gave enough of a damn about The Beatles to insist that they maintain their extraordinarily high standards.

As with the Klein thing a little further on, was he not more right than wrong in all this? He knew how special this ‘good little group’ of theirs was, and it distressed him terribly to see the Yoko-besotted John and the more and more individuated George drifting away. Yes, Paul could be pig-headed. He could be obnoxious. Bossy even. But he was surely less narcissistic and less mean-spirited in this period than John or George. He never stopped feeling blessed to be in a room with these three guys, because he never stopped appreciating just how much bigger the sum of the parts was. The Beatles’ very reputation, legacy and continued existence remained his priority. Even a dose of unequivocal and consistent moral support from Ringo would have made the role he had assumed a good deal less lonely and thankless.

The end of touring; Brian’s death; Yoko’s arrival; the band’s financial disarray; George’s growing peevishness; and Paul’s increasing isolation: it amounted to a perfect storm. But in the end it comes back, one feels, to John. As already suggested, he was damned lucky to make it out of the Sixties alive. Acid had taken from him even as it had given. There was no free lunch. What with the buried traumas of his childhood and teen years, and the insecurities proper to his idiosyncratic and outsized personality, it left him prone to mood swings and by turns grandiose and depressive episodes. (At one point, he called a meeting at Apple to announce that he was Christ Jesus returned.)

Acid, in short, may well have been the thing which, more than anything else, deprived the Seventies of The Beatles. John had effectively resigned his role as leader and even co-leader of The Beatles, and then put great energy into blaming Paul for his own passivity. This in turn left Paul exposed to George’s growing junior-sibling bitterness.

In the Anthology documentary, Paul explains his decision not to get too heavily into acid. He feared, he says, that he would “never get back home again.” Get back home: it’s an interesting choice of words. John thought Paul’s hit-making line, “Get back to where you once belonged”, was a dig at Yoko. Perhaps it was actually a forlorn plea, conscious or unconscious, to John himself to find his way back home to being a Beatle. But, for John, irrevocably changed by acid, The Beatles were no longer the home where the heart was.

“You and I have memories longer than the road that stretches out ahead…” You’re not coming home, are you, John?

Related articles:

- The Making of Revolver

- The Making of Paul McCartney's Ram

- Geoff Emerick — The Real Beatles Producer?

About the author

Daragh Downes is a writer, critic and musician. He has written music features and reviews for The Irish Times and has discussed musical, literary and cultural matters on Irish national radio. For many years he lectured on literature, aesthetic theory and cultural history at Trinity College, Dublin.