It's a boringly drama-free affair

In one sense, the recording of David Bowie’s fifth studio album, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, was a boringly drama-free affair.

Having just recorded Hunky Dory at Trident Studios with musicians Mick Ronson, Trevor Bolder, Mick ‘Woody’ Woodmansey and Rick Wakeman, and with co-producer Ken Scott, Bowie lost little time in going straight back into the same studio with the same team (minus Wakeman) and laying down another bunch of tracks.

By all accounts, the sessions were a happy experience, with everyone working quickly and confidently. The sound was tougher and crisper than on Hunky Dory. Ronson enjoyed more scope to crank it up on his Les Paul, and Woodmansey was much happier with the drum sound Scott was able to achieve on this album. Apart from ‘Suffragette City,’ ‘Rock ’n’ Roll Suicide’ and ‘Starman,’ all the tracks that would make it on to the newer-than-new album were in the can before Hunky Dory was even in the shops.

If an obvious question arises from the above, it is surely this: why did Bowie, fresh from the triumph of the Hunky Dory sessions, feel the need to get back into the studio so quickly?

Well, the man was on a roll and he knew it. At the heart of his new manager Tony Defries’ plan for scoring a record deal with a major label had been the bold strategy: you build the cart and I’ll get you the horse. The Hunky Dory sessions had gone great, and Defries had done great. This had only set the ever-restless Bowie thinking. Why not use this brilliant team to make the cart bigger? Heck, why not build a second cart, for attaching behind the first one? Either way, it will make the case for a well-fed horse.

While this thinking may explain Bowie’s decision to go back and record some more tracks so soon, it hardly explains the musical turn away from Hunky Dory that these new tracks represent. In terms of team and location, the Ziggy sessions are a continuation of the Hunky Dory sessions; musically, however, they yield a strange non sequitur.

For starters, they showcase a return to guitar-based composition.

Side A of Hunky Dory had heavily favoured the first fruits of Bowie’s recent discovery of the excitements of writing on piano. This breakthrough had taken him to new places chordally and texturally, and no better man than Rick Wakeman to bring out further dynamic possibilities in studio. But now, as he faced into the recording of another suite of tracks, Bowie took a calculated step ‘backwards.’ He wanted the more primitive adrenaline rush of ‘Queen Bitch’ to be the definitive vibe on the new album.

Why? Could he possibly have been unhappy with the remarkable and soon-to-be-released Hunky Dory?

No and yes. He knew Hunky Dory was an artistic triumph. But artistry was only ever one side of the equation for him. He wanted commercial success and fame, those two amplifiers without which no exercise in artistry would get heard with due attention. He already sensed — correctly, as it would turn out — that Hunky Dory would not do the business in the record shops. A music-business veteran by this stage, he had seen too many strong musical efforts of his fail to land commercially. He was absolutely determined, this time round, to end up on the right side of the fine line dividing noble failure and nobler success.

Two thoughts must have been uppermost in his tactical brain.

First, kinetic energy: I need more out-and-out rock ’n’ roll songs that will go down a storm live.

Second, thematics: What better way to materialise the stardom I dream of than to sing and stage that very phenomenon?

The compositional and performance mastery on show on Hunky Dory was all well and good, but for the level of success Bowie dreamed of what was needed was musical and theatrical voltage. It was time to pretend. At very high volume.

In November 1977, in an interview with Eddie & Flo for Canadian TV, Bowie would offer the following gloss on Ziggy:

“I wanted to define the archetype Messiah Rockstar. That’s all I wanted to do, and I used the trappings of kabuki theatre, mime technique, fringe New York music — like, my references were Velvet Underground, whatever… So, Ziggy was for me a very simplistic thing. It was what it seemed to be: an alien rockstar, and for performance value I dressed him and acted him out. I left it at that, but other people re-read him and contributed more information about Ziggy than I’d put into him…”

He’s being a little disingenuous in this last bit. He himself had peddled elaborate explanations of the Ziggy ‘concept’ to people (especially people called William Burroughs), gamely name dropping “the infinites,” “black-hole jumpers,” et cetera. He had openly mulled a story-driven Broadway-worthy production. He himself had been, in large part, responsible for so many people falling prey to the enticing retrospective illusion: the whole Ziggy album as a carefully calculated concept affair from the start.

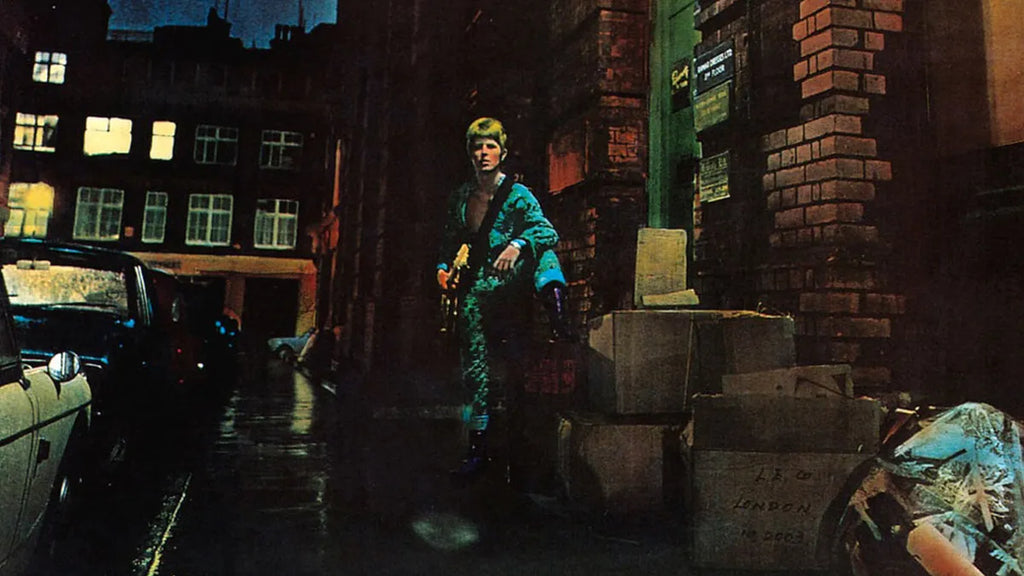

David Bowie as Ziggy Stardust, performing in Newcastle in 1973. Photo: Trinity Mirror / Mirrorpix / Alamy

A loose concept album and rock opera

Let’s get our bearings by taking a peek at the current Wikipedia overview of The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars:

“Described as a loose concept album and rock opera, Ziggy Stardust is about Bowie's titular alter ego, Ziggy Stardust, a fictional androgynous and bisexual rock star who is sent to Earth as a saviour before an impending apocalyptic disaster. In the story, Ziggy wins the hearts of fans but suffers a fall from grace after succumbing to his own ego. The character was inspired by numerous musicians, including Vince Taylor. Most of the album's concept was developed after the songs were recorded.”

The key word here, for our present purposes, is “loose” in sentence one; the most important sentence the last one. Over the course of its evolution, preparation for release, and exposure to the world, the Ziggy album underwent an inspired transformation in status from ballsy follow-up to Hunky Dory to big bang of a standalone new mythology. The arrival of the sublime ‘Starman’ song in January/February ’72 (in response to RCA’s complaint that the follow-up album lacked a hit single) made possible the construction, post hoc, of the album’s supposedly defining Starman conceit.

Imagine a different sequence of events: Bowie has just recorded Hunky Dory, and is so pleased with it he decides to ‘develop’ its ‘concept.’. No follow-up album needed — yet. What, in this alternate universe, might our Wikipedia gloss look like? Let’s be naughty and give it a go:

“Described as a loose concept album and rock opera, Hunky Dory is about Bowie's titular alter ego Hunky Dory, a fictional androgynous and bisexual rock star from Mars who is sent to Earth as a saviour before an impending apocalyptic disaster. In the story, Hunky wins the hearts of fans but suffers a fall from grace after succumbing to his own ego. The character was inspired by numerous musicians, including Vince Taylor. Most of the album's concept was developed after the songs were recorded.”

Easy, innit? And can one really doubt that our virtual David Bowie, being David Bowie, will get away with it? The ‘Ziggy’ look is developed with the help of Angie and Freddi Burretti, only the character is given the name Hunky Dory. A touch of kabuki, a hint of Clockwork Orange Droog, a Kansai Yamamoto-inspired hairstyling in late-January ’72 courtesy of Suzi Ronson, and — presto.

Bowie can simply stick ‘Quicksand’ at album’s close, and fans will be able to track the ‘Hunky narrative’ across the album: an expectant counter-cultural youth (‘Changes,’ ‘Oh! You Pretty Things,’ ‘Eight Line Poem,’ ‘Life on Mars?’, ‘Kooks’) attracts, by very dint of its yearning, the new Starman-Messiah, who preaches love and liberation (‘Fill Your Heart’), seeks out human prophets (‘Andy Warhol’, ‘Song for Bob Dylan’), before succumbing to corruption, disillusionment and eve-of-apocalypse mental breakdown (‘Queen Bitch’, ‘The Bewlay Brothers’, ‘Quicksand’).

Indeed, we could go further with our little alternate history game. Let’s suppose the wheels have not already been put in motion for the December ’71 release of Hunky Dory. Bowie and team record the Ziggy tracks, but with Hunky retained as the Starman protagonist (“Hunky played guitar…”).

The glorious result is a double album, The Rise and Fall of Hunky Dory and the Playboys From Mars, which represents the soundtrack for a rock opera to out-Tommy Tommy. Disc One covers the period of messianic expectation and societal disorientation:

Side A

- ‘Changes’

- ‘Oh! You Pretty Things’

- ‘Eight Line Poem’

- ‘Life on Mars?’

- ‘Kooks’

- ‘Quicksand’

Side B

- ‘Fill Your Heart’

- ‘Andy Warhol’

- ‘Song for Bob Dylan’

- ‘Queen Bitch’

- ‘The Bewlay Brothers’

Disc Two gives us Hunky’s end-of-days arrival on earth, rock-star existence and eventual fall from grace:

Side C

- ‘Five Years’

- ‘Soul Love’

- ‘Moonage Daydream’

- ‘Starman’

- ‘It Ain’t Easy’

Side D

- ‘Lady Stardust’

- ‘Star’

- ‘Hang on to Yourself’

- ‘Hunky Dory’ (for ‘Ziggy Stardust’)

- ‘Suffragette City’

- ‘Rock ’n’ Roll Suicide’

A ‘loose’ ‘concept’? Sure, but scarcely any looser than the Ziggy gambit Bowie actually went with.

We would do well, in short, to distinguish between Bowie’s post-recording mythologisation of Ziggy (and Ziggy) and what was in and on his mind as he and his team laid down the tracks at Trident.

As to the latter, here are a few telling clues to get going with.

- One of the tracks to make it on to Ziggy had already been recorded during the Hunky Dory sessions: ‘It Ain’t Easy’ (Bowie’s cover of the Ron Davies country-gospel song). It featured Rick Wakeman on harpsichord.

- Four songs from the pre-Hunky Dory Arnold Corns sessions were revisited in the Ziggy sessions: ‘Moonage Daydream,’ ‘Hang on to Yourself,’ ‘Lady Stardust’ and ‘Looking For A Friend.’ (Arnold Corns being Bowie's short-lived 1971 band project.)

- Chuck Berry’s song ‘Around and Around’ was recorded (under the title ‘Round and Round’) for Ziggy, only getting bumped at the eleventh hour by ‘Starman’. Indeed, the album’s original working title was Round and Round (geddit?).

- During the Ziggy sessions, a song from Bowie’s underperforming third album, The Man Who Sold the World, was re-recorded: ‘The Supermen.’

- ‘Holy Holy’, the flop single recorded after The Man Who Sold The World and released in January ‘71, was re-recorded.

- In January ’72 Bowie offered ‘Suffragette City’ to Mott the Hoople. When they said no, he went and recorded it for himself.

Does the above suggest a man with a bold and compelling new story to tell? Hardly. Bowie is in fact casting around for older material that he can re-heat. He is of course buzzing with excitement at the newer stuff he has written, but his approach is far from blank-slate. Rather he feels a growing assurance with his current team, coupled with a desire to get them on the road with rockier material than that showcased (with the exception of ‘Queen Bitch’) on Hunky Dory. He is anything but precious — or programmatically-bound — about where the ‘new’ material comes from. He will work with whatever works.

Gonna rock it up (again)

And here the plot thickens further. Bowie has already rocked up his sound once before, on The Man Who Sold the World. The big difference between it and what will be Ziggy? Circumstances, dear boy. Who knows what the Tony Visconti-produced The Man Who Sold The World might have done for Bowie had Tony Defries been looking after him last year? Or what he might have done had that album’s release been cancelled due to trouble with his then-label(s), Mercury/Philips?

If judged on purely musical grounds, and circumstances allowing, there would arguably have been more logic in Bowie’s owning the early Seventies with a very different album release schedule:

- Summer ’72: Ziggy Stardust (as is).

- Winter ’72: The Man Who Sold the World (re-recorded in part or in full with Ronson, Bolder and Woodmansey, with Ken Scott on co-production, and returned to its original title, Metrobolist).

- Summer ’73: Hunky Dory (as is).

Would not such a chronology have borne more discernible marks of musical progression? Would there not have been much greater sonic, stylistic and thematic continuity between Ziggy and Metrobolist than between The Man Who Sold The World and Hunky Dory? And much greater sense of progression between Metrobolist and Hunky Dory than between Hunky Dory and Ziggy? Hard not to imagine people being stunned by Hunky Dory as album number three from the resurrected, RCA-backed David Bowie. The critics would have raved. “We didn’t think he could top Ziggy and Metrobolist, but he just has. We haven’t seen this kind of artistic leap since Rubber Soul to Revolver…”

If history is written by the winners, then music history likes to read artistic value into worldly success. Ziggy’s popular eclipsing of Hunky Dory and The Man Who Sold the World wasn’t necessarily fair.

In the event, Bowie has to release Ziggy after Hunky. What Ziggy shows is Bowie engaged in a tense double move: less range on the musical front, but no letting up on the lyrical sophistication front.

Consider the lyrical changes he has made in the verses of ‘Hang on to Yourself’ and ‘Moonage Daydream’, two Arnold Corns songs to make it on to the album.

‘Hang on to Yourself’, Arnold Corns version:

Father had a good thing going, and you know, mama had a thing on

My baby got out last Monday, and me I’m on a radio show

[…]

My father had a good thing going, and you know mama had a thing on the street

My baby got out last Monday, and me I’m on a radio show

Ziggy version:

Oh, she's a tongue twisting storm

Comes to the show tonight

Praying to the light machine

She wants my honey, not my money

She's a funky-thigh collector

Laying on electric dream

[…]

We can't dance, we don't talk much, we just ball and play

But then we move like tigers on Vaseline

Well, the bitter comes out better on a stolen guitar

You're the blessed, we're the Spiders from Mars

‘Moonage Daydream’, Arnold Corns version:

Keep your mouth shut, but listen to the word inside

Keep your head on, but open up your eyes real wide

Keep the change strong, let the things you've torn aside

There isn't any room to hide

Ziggy version:

I'm an alligator

I'm a mama-papa comin' for you

I'm the space invader

I'll be a rock 'n' rollin' bitch for you

Keep your mouth shut

You're squawking like a pink monkey bird

And I'm bustin' up my brains for the words

What has happened? Bowie, re-emboldened by the Hunky Dory experience, is making sweet love to concrete nouns. Evocative specificity has trumped abstraction and metaphysics. He wants, as it were, to cultivate a Chuck Berry eye and train it with fearless idiosyncrasy on the Seventies.

The wild mutation

But something else, something deeper, is in the thematic mix: Bowie’s own all-consuming desire for stardom.

If Ziggy gives vent to a preoccupation greater even than the extraterrestrial conceits that have long fascinated Bowie, then that preoccupation is stardom in the celebrity sense. With the old gods in retirement, and modernity reducing us to the level of Nietzsche’s “last man”, stardom offers itself as the only viable alternative to a life lived in the mundane world. It is the new royalty. To be a star is — as the word suggests — to be in the world but not of it. Ziggy is an album not so much about an alien who falls to earth as about a human who feels the earth’s fallenness in every cell of his body, and longs to be granted the exemption granted only to the very special few.

(Just a few months after Ziggy's release, the New York Times reviewer of Presley at Madison Square Garden will describe The King on stage as being “like a prince from another planet.”)

The rockstar Übermensch needs ordinary people to need him, whilst also needing to float free of their ordinary world.

A couple of years back, in ‘Memory of a Free Festival’, Bowie sang bittersweetly about the hippy dream of merging ecstatically with the collective:

We claimed the very source of joy ran through

It didn’t, but it seemed that way

I kissed a lot of people that day

[…]

Someone passed some bliss among the crowd

[…]

The Sun Machine is coming down, and we’re gonna have a party

On Ziggy’s opening track, ‘Five Years’, the lyrical I confesses he “never thought I’d need so many people.” Their very ordinariness is what has suddenly become precious to him.

But love? Real love? Relationship? Forget it. Too delusorily human, too immersive. Too inimical to specialness. “All I have is my love of love,” Bowie sings on ‘Soul Love,’ a song whose lyrical I can never be anything more than a cold voyeur of love, a connoisseur of meta-love. “Stone love… New love… Soul love… Idiot love”: so many traps for the human animal. “Lie lie lie lie lie….” taunts the song’s outro.

There is only one thing that promises escape: the miracle status of stardom. Thus the opening of the song ‘Star’: “Tony went to fight in Belfast,/ Rudi [!] stayed at home to starve,” but… “I could make it all worthwhile/ As a rock ’n’ roll star.” This is Nietzsche’s aesthetic justification of existence, and the current album is a bid to make Bowie’s own existence all worthwhile by recording song after song about a life lived in accordance with that doctrine. The grandiosity of stardom is the compensation strategy of choice for the outlier soul in despair at finding himself just another perishable human being on crowded planet earth. Stardom is an aesthetic answer to what, in an earlier era, would have been classed as religious despair. It is an attempt to steal transcendence. The rock ’n’ roll star transcends by virtue of his difference, his alterity, his alienness.

Actually… why not literalise this last idea? In this more positivistic era, does not an alien from outer space suggest itself ahead of a Jesus Christ Superstar as the symbolic avatar of rock ’n’ roll salvation? A respectably materialist messiah.

Allied to all this, of course, is Bowie’s shrewd grasp of the psychology of fandom. He’s been there himself, from at least the time his dad took him to see Tommy Steele. The star offers the fan vicarious escape from their own administered, aggregated existence. He is a figure onto whom the fan can project their own gold, a vehicle for their own dreams of a life less ordinary.

Time takes a cigarette

Stardom, then, as the prime sponsoring myth of Ziggy, with Starman offering a narratively suggestive play on words. And such is Bowie’s realism and self-awareness, he recognises this myth for what it is: a tragic myth.

A few years back he ran into Middlesex-born ‘American’ Elvis imitator Vince Taylor, a man already on the far side of acid-triggered psychological disintegration. As Bowie will recall for Alan Yentob in 1996:

"I met him a few times in the mid-Sixties, and I went to a few parties with him. He was out of his gourd. Totally flipped. The guy was not playing with a full deck at all. He used to carry maps of Europe around with him, and I remember him opening a map outside Charing Cross tube station, putting it on the pavement and kneeling down with a magnifying glass. He pointed out all the sites where UFOs were going to land."

Bowie, always alive to the pathos of beyond-the-pale outsiderdom, was gifted, in a way he didn’t fully understand at the time, with the potent association: Rock ’n’ Roll Star – Aliens – Bonkers.

Which is where the extraordinary closing track on Ziggy, ‘Rock ’n’ Roll Suicide,’ comes in, at least kind of. Bowie already knows the “I’ll be a star!” route out of Weltschmerz is too fraught with contradictions and evasions to be anything other than an ultimately self-defeating solution. You want to escape your human beingness by relying on the adulation of human beings? Good luck with that, boy.

As Bowie would recall later, Taylor’s “music was pretty pony”, but “he was definitely part of the blueprint of this strange character that came from somewhere.” No doubt. But my suspicion is that this blueprint only really came into some sort of proper focus with ‘Starman’ in January. The break in work on the album between mid-November ’71 and early January ’72 may have given him a crucial incubation period for his ideas.

As of Christmas ’71, by which time Hunky Dory had already been released, Bowie had all but made Round and Round, an album that had done no less but no more than allow him to

- foreground the theme of rock ’n’ roll fame

- exploit to the full the remarkable talents on hand by cutting some lyrically-warped rock ’n’ roll tracks apt to electrify live audiences

- indulge, here and there, and yet again, his confirmed penchant for extraterrestrial themes and images.

Listen to the Ziggy album without ‘Starman’, and you may well be hearing the sound of Bowie returning for another try at the Plan A he had developed when the inestimably talented and endlessly helpful Mick Ronson first came into his orbit. Round and Round, on this hypothesis, was conceived above all else as a grudge match against the cloth-eared nincompoops who had given The Man Who Sold The World their undivided inattention. It was recorded by a man who didn’t yet look anything like Ziggy Stardust — a man who desperately wanted to sell to the world.

My guess: already by November ’71, Bowie wished he wasn’t bound in to the release schedule for Hunky Dory. He couldn’t nix that schedule, but he ended up doing the next best thing: he changed his sound and his look, and went pretty much all in on the follow-up album. RCA’s desultory promotional push for Hunky Dory found an all too willing accomplice in its creator.

Far from disowning Hunky Dory, however, Bowie was in fact trying to create the real-world conditions under which it could find the mass audience he knew it deserved. For he understood intuitively that the world needed shocking into attention before it would come to appreciate the panoply of riches on offer in Hunky Dory (and, into the bargain, The Man Who Sold The World). Enter Ziggy — and Ziggy.

Not until a certain appearance on Top of the Pops that following summer would the full dialectical genius of this high-risk manoeuvre begin to disclose itself...

You might also enjoy:

- The Making of David Bowie's Hunky Dory album

- David Bowie Movies — A Guide to All His Cinema Roles

- The Making of The Beatles' Revolver album

About the author

Daragh Downes is a writer, critic and musician. He has written music features and reviews for The Irish Times and has discussed musical, literary and cultural matters on Irish national radio. For many years he lectured on literature, aesthetic theory and cultural history at Trinity College, Dublin.